What is sickle cell anaemia?

Sickle cell anaemia is the most well-known and common type of sickle cell disease, in which the blood disorder results in anaemia (a shortage of haemoglobin and/or red blood cells in the blood, reducing the amount of oxygen carried by the blood to the cells that need it).

Haemoglobin is a protein found in red blood cells that binds to oxygen, allowing them to carry it around the body to cells that need it to function and grow.

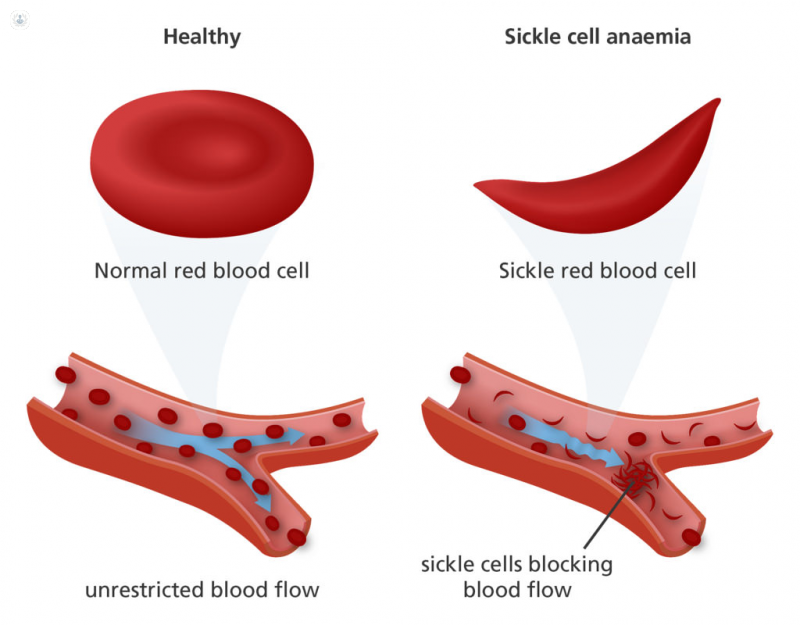

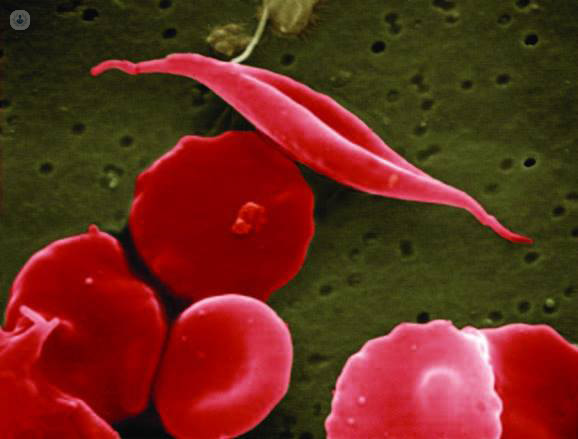

In sickle cell anaemia, haemoglobin forms stiff rods inside the red blood cells, making them rigid and inflexible. While red blood cells are usually round, flexible donut-like structures that pass easily through blood vessels, sickle cells are curved and inflexible due to the rigid haemoglobin, and frequently get stuck, clogging blood vessels and causing pain and damage.

What are the symptoms of sickle cell anaemia?

While red blood cells are usually replaced every 120 days, sickle cells die much faster, typically lasting 10-20 days, causing a shortage of red blood cells, and therefore, a shortage of oxygen to the rest of the body. This causes classic symptoms of anaemia, such as:

Other symptoms of sickle cell anaemia include:

What causes sickle cell anaemia?

Sickle cell anaemia is a genetic condition. It is caused by a mutation in the gene that codes for haemoglobin. We all inherit two copies of each gene – one from each parent. Sickle cell anaemia is recessive, which means that both of the patient’s copies of the haemoglobin gene must be the mutated form known as “haemoglobin S” for the condition to manifest (meaning that both parents either had the condition themselves, or were carriers).

Individuals who have one normal and one mutated copy of the gene will have sickle cell trait, which means they produce both normal and sickle cell haemoglobin. Their blood may contain a combination of normal red blood cells and sickle cells, but symptoms don’t usually manifest. However, they carry the possibility of passing it on to their children.

What is the treatment?

Treatment is generally geared towards managing pain crises and preventing infection, and any other complications caused by sickle cell anaemia. It is important for the patient to be monitored, with regular eye exams and tests for pulmonary hypertension.

The only “cure” is a bone marrow transplant, which involves destroying the patient’s stem cells and replacing them with that of a donor. Stem cells can develop into any cell, as required by the body, and in theory, stem cells from a donor who doesn’t have sickle cell anaemia should develop into healthy, normal red blood cells. However, donors must be blood relatives, and even then, there is a risk the patient’s body will reject the donated stem cells. The risk of complications is greater the older the patient gets, and as such this treatment is performed more frequently on children than adults. Even so, with the shortage of viable donors and the risks involved, the procedure is relatively uncommon.