Water on the brain: a guide to hydrocephalus

Also called as ‘water on the brain’, hydrocephalus is an excessive accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid on the brain, causing abnormal dilation of brain spaces known as ventricles. This exerts a damaging pressure on the brain, which usually needs to be treated with a bypass system or catheter with a valve.

What is Hydrocephalus?

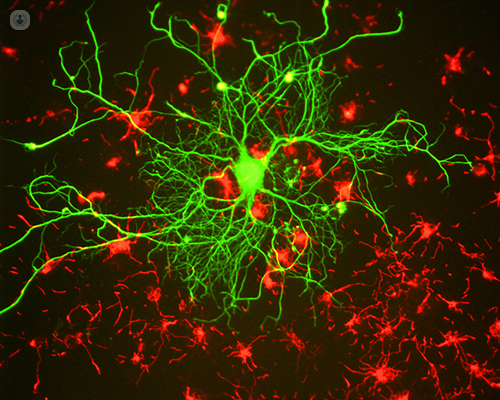

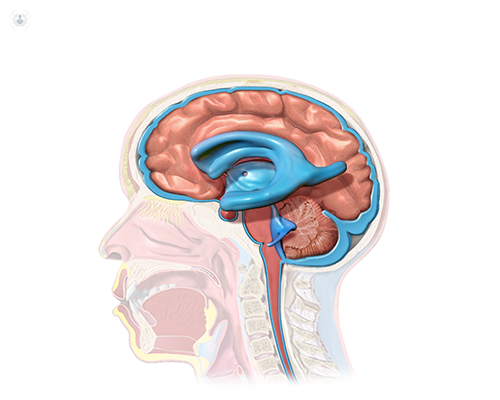

Hydrocephalus comes from the Greek "Hidro" (water) and "cefalo" (head). Its characteristic is the excessive accumulation of fluid on the brain. However, this ‘water is actually cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), a clear fluid that envelops the brain and spinal cord. Too much of CSF causes abnormal dilation of the cerebral ventricles and a damaging build-up of pressure on the brain.

The ventricular system of the brain consists of four connected ventricles. Normally, the CSF flows through them, exits into cisterns (enclosed spaces that serve as reservoirs) at the base of the brain, bathes the surface and spinal cord and then is reabsorbed into the bloodstream.

The CSF has three vital functions:

1) Floating around the brain structure, it acts as a mattress or shock absorber

2) It serves as a vehicle to transport nutrients to the brain and eliminate waste

3) It flows between the skull and spine, to compensate for changes in the volume of blood within the brain.

The balance between the production and absorption of CSF is of vital importance. Ideally, the fluid is almost completely absorbed into the bloodstream as it circulates. However, there are circumstances that prevent or alter the production of CSF, inhibiting its normal flow. Hydrocephalus happens when this balance is disturbed.

Types of hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus may be congenital or acquired. The first type appears during gestation and can be caused by environmental influences during the development of the foetus or by genital predisposition. Acquired hydrocephalus develops after birth.

Hydrocephalus is also further classified as communicant or non-communicant:

- Communicant hydrocephalus: occurs when the CSF flow is blocked after exiting the ventricles. It is so named because the CSF can still flow between the ventricles, which remain open.

- Non-Communicant (or Obstructive) hydrocephalus: occurs when the CSF flow is blocked along one or more narrow pathways that connect the ventricles. One of the most common causes of hydrocephalus is “aqueduct stenosis", a case resulting from a narrowing of the Silvio aqueduct, a small conduit between the third and fourth ventricles in the middle of the brain.

There are two more forms of hydrocephalus that do not fit into the above-described categories, and mainly affect adults:

- Hydrocephalus ex vacuo: occurs when there is damage in the brain, caused by a stroke (stroke) or a traumatic injury. In these cases, there may be a true contraction (atrophy or emaciation) of the brain tissue.

- Normal pressure hydrocephalus (chronic hydrocephalus of the adult): occurs in elderly people and is characterised by many symptoms associated with other conditions that often occur in the elderly: memory loss, dementia, gait disorder, urinary incontinence and general reduction in ability to carry out daily life.

How common is hydrocephalus?

It is difficult to establish data on the incidence and prevalence of hydrocephalus since there is no national registry of patients suffering from hydrocephalus or associated diseases. However, hydrocephalus is believed to affect 1 in 500 children. Currently, the majority of cases are diagnosed prenatally, at the time of birth or in early childhood. In addition, advances in diagnostic imaging technology make it possible to detect it more accurately in people with atypical presentations.

Causes of hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus can result from genetic inheritance (developmental disorders) or developmental disorders, such as those associated with defects in the neural tube (including Spina Bifida and Encephalocele).

Other possible causes are:

- Complications of premature birth (ventricular haemorrhage, for example)

- Diseases such as meningitis

- Tumours

- cranial trauma or subarachnoid haemorrhage that blocks the ventricles, prevents CSF from exiting the cisterns and eliminates (closes) the cisterns themselves

Symptoms of hydrocephalus

Symptoms vary with age, disease progression and individual differences in CSF tolerance. A clear example is that a child does not have the same capacity as an adult to tolerate CSF pressure. A child's skull may expand to accommodate increased CSF because the sutures (fibrous joints connecting the bones of the skull) have not yet fused.

In childhood, the obvious indication of hydrocephalus is the rapid increase in head circumference or too large a head size. Other symptoms may include: vomiting, sleepiness, irritability, downward deviation of the eyes and convulsions.

Older children and adults may experience different symptoms because their skull cannot expand to accommodate increased CSF. Aside from vomiting, other symptoms may include: papilledema (swelling of the optic disc part of the optic nerve), blurred vision, diplopia (double vision), downward deviation of the eyes, balance problems, poor coordination, walking disorder, incontinence, urinary retention, reduction or loss of development, lethargy, drowsiness, irritability or other changes in personality and brain functions such as memory loss.

Diagnosing hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus is diagnosed by clinical neurological evaluation and cranial imaging techniques, such as:

- Ultrasound

- computed tomography (CT)

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Techniques for recording intracranial pressure

The Neurosurgery expert will select the appropriate diagnostic tool based on age, clinical presentation and presence of known or suspected abnormalities of the brain or spinal cord.

Treatment of hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus is treated by a bypass implant known as shunt surgery. The bypass system diverts the flow of CSF from the central nervous system to another area of the body where it can be absorbed as part of the circulatory process.

The bypass is a flexible yet robust system consisting of an elastic tube, a catheter and a valve. One end of the catheter is inserted into the central nervous system (inside the ventricle inside the brain or inside a cyst or inside the spinal cord). The other end of the catheter is normally placed inside the abdominal cavity, but can also be placed in other parts of the body, such as in a heart chamber or in a pulmonary cavity where the CSF can drain and be absorbed. The valve positioned along the catheter maintains the flow in one direction and regulates the amount of CSF flow.

Alternatively, a limited number of patients can be treated with a different procedure, called a ventriculostomy. In this procedure, a neuroendoscope (a small camera designed to visualise small surgical areas that are difficult to access) enables the surgeon to see the ventricular surface. The neuroendoscope is guided so that a small hole can be made in the third ventricle, allowing the CSF to pass the obstruction and flow to the reabsorption site around the surface of the brain.

Possible complications of the referral system in the treatment of hydrocephalus

Bypass systems are not perfect mechanisms. Complications such as mechanical failures, infections, obstructions, and the need to prolong the life of or replace the catheter may arise. The system usually require regular medical monitoring and follow-up and, if there are complications, adjustments or revisions are carried out. Review is important because complications can lead to excessive or insufficient drainage.

Excessive drainage occurs when the bypass allows CSF to drain the ventricles more quickly than it accumulates. This can cause the ventricles to collapse, rupturing blood vessels and causing headache, bleeding (subdural haematoma), or cleft ventricles.

Insufficient drainage, on the other hand, occurs when the CSF does not drain fast enough and the symptoms of hydrocephalus reappear. Additionally, infections of a bypass can lead to other symptoms such as fever, pain in the muscles of the neck or shoulders, and redness or tenderness along the path of the shunt.

If there is a suspicion that a bypass system is not working properly, immediate medical attention should be sought.

Hydrocephalus prognosis

The prognosis in patients with hydrocephalus is difficult to predict, although there is some correlation between the specific cause of hydrocephalus and the outcome of the condition. The prognosis is complicated by the presence of associated disorders, being able to make an early diagnosis and the success of the treatment.

However, the extent to which decompression (pressure relief or CSF increase), after shunt surgery, can reduce or reverse damage to the brain is not well understood.

Affected individuals and their families should be aware that hydrocephalus poses risks to physical and cognitive development. However, many diagnosed children benefit from rehabilitative therapies and educational interventions that help them lead a normal life with few limitations. In this sense, treatment with an interdisciplinary team of medical professionals, rehabilitation specialists and educational experts is vital for a positive outcome.

Treatment of hydrocephalus saves the life of the patient. If left untreated, progressive hydrocephalus, with rare exceptions, is fatal.

Research into the condition

One area of research of hydrocephalus is examining the intellectual development, the academic results and the behaviour of the children with the condition. Researchers are hopeful that this new study will shed light on the influence of hydrocephalus on development, as well as the effect of early brain injury.

Another study is examining an adjustable valve system. The goal of the study is to create a valve system that reduces the number of bypass system revisions.

Knowledge gained from such studies will provide the basis for understanding how this process may fail and, therefore, offers hope of new means to treat and prevent developmental brain disorders, such as hydrocephalus.